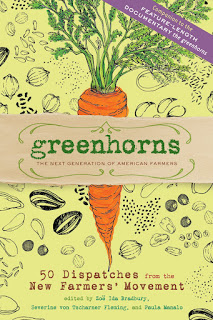

We’re thrilled to finally have our hands on “Greenhorns: The Next Generation of American Farmers,” a new book by our friends, The Greenhorns. Editors (and fellow Greenhorns) Severine Von Tscharner Fleming, Zoë Bradbury and Paula Manalo have gathered up 50 compelling, funny, heartbreaking and hopeful stories from beginning farmers around the country. Each story gives the reader the opportunity to spend some time in a farmer’s boots, and each tale reveals an aspect of the challenges and triumphs new farmers face. These are great stories that can be passed along for the lessons they hold.

We’re thrilled to finally have our hands on “Greenhorns: The Next Generation of American Farmers,” a new book by our friends, The Greenhorns. Editors (and fellow Greenhorns) Severine Von Tscharner Fleming, Zoë Bradbury and Paula Manalo have gathered up 50 compelling, funny, heartbreaking and hopeful stories from beginning farmers around the country. Each story gives the reader the opportunity to spend some time in a farmer’s boots, and each tale reveals an aspect of the challenges and triumphs new farmers face. These are great stories that can be passed along for the lessons they hold.

The following excerpt is from a story that is right up our alley. It illustrates perfectly the American farmer’s ingenuity, tenacity and disregard for the concept that something is “impossible.” Teresa and her partner, Packy, dreamed of owning their own land to farm, and had finally found the perfect property for them. They were ready to buy and started the process in what they thought was the “right” way. Turns out that the “right” way wasn’t going to work for a farmer. The excerpt picks up there:

I’d like to meet the farmer who can buy a piece of land, till it, prepare the soil, sow the seeds, grow the plants, harvest the crop, take the crop to market, sell it, deposit the cash in the bank, and write a check for the mortgage all in one month. In October. On the Oregon coast.

Hoping to talk to people who at least understood the physical realities of farming, we called the USDA Farm Service Agency about its small-farm loan program. The FSA agent we met with listened to our plans, then paid us the compliment of saying that it seemed like we actually had our act together. But she went on to be brutally honest about the FSA small-farm loan program and our chances of actually getting a loan to buy land for our farm. To her, a small farm was one growing four hundred acres of grass seed or running three hundred head of cattle. She told us that our proposed five or six acres of cultivated land growing mixed vegetable, fruit, and flower crops, and raising chickens with some off-farm income rounding out the economic edges fell into the USDA category of a “lifestyle farm.”

“We don’t normally make loans for lifestyle farms,” she told us politely.

“It’s a damn hard way of life, not a bloody lifestyle,” I muttered, annoyed, on the subdued drive home.

The seller of the farm we loved still wanted a crazy amount of money for it, and we had no loan options that would let us even begin negotiating, so she stopped talking to us and we sadly tried to accept that we were just never going to farm that land.

We spent the next six months scrambling, trying to come up with some way to keep farming on the Oregon coast. We had market customers calling us with land-for-sale referrals and offering to sign up for a CSA program before we even had a farm to grow the food. We explored many, many ideas: buy land with a group of people and start a nonprofit education farm; temporarily lease another piece of land; find a cheaper land option; renegotiate with our current landlords; borrow money privately. Each option was explored and each gradually disintegrated as we tried to cobble together a solution to keep our dying farm alive, all painfully in the midst of our best market season ever.

A grim day in June found us sitting at the kitchen table facing the bleak reality that we were going to have to quit farming. It was a painful moment for me. At forty-three years old I had finally found work I loved, work I was actually good at and that I cared passionately about. I could grow plants, I could feed people, and I could teach them how to grow plants and feed themselves. The support from our community for the farm we wanted to have was heartening to us, but it couldn’t get us the loan we needed. With deep resignation, we each made phone calls, went for interviews, and accepted “real jobs” with the understanding that we would start part time to allow us to finish out the current farmers’-market season, pay off bills, and put the farm into hibernation.

Farm or no farm, we needed to find a new place to live. While cruising around online to figure out what kind of house price we might be able afford with our new job income, we stumbled across a local real-estate company on whose home page under the heading NEW LISTINGS was that farm. The farm we loved. The farm we’d tried to buy for more than a year, the land we’d dreamed about and planned for and had finally, depressingly given up on some six months ago. Still for sale. Price reduced to something we could now maybe afford.

In a daze, we called a local bank and made an appointment to talk about a straight-up, super-normal home loan. We told our long story to the very nice broker, reassured him about our commitment to our regular-paycheck “real jobs,” described the down-payment fund we had waiting, and explained our plan for keeping the farm going part time to help with additional income to pay the mortgage.

“No farming,” he said sternly. “Quit the farming, right now. Only work the regular-paycheck real jobs. Then, maybe, we can make it work.”

So that’s what we did. The irony of having to quit farming so we could finally get a loan to buy the land to move our farm to stuck in our craw, and was made even harder to swallow when we had to provide written reassurance to the lenders (nervous about our worrisome “history of farming”) that although we had indeed spent five years running a “hobby farm,” we had seen the error of that life path, now had nice safe real jobs, and only wanted to buy eighteen acres of land zoned agriculture-forestry so we could continue to live a “rural lifestyle.”

It wasn’t a legally binding document, and besides, I had my fingers crossed behind my back when I signed it. I can’t say I recommend lying to your bank as a road to farm ownership, but it worked, and I’m not ashamed that that’s what we did. The shame I feel is for a country that makes it virtually impossible for hardworking beginning farmers — people who are willing to devote their lives to growing healthy food for their communities — to own land.

We’re still working off-farm to make ends meet, slowly building our soil, rebuilding our infrastructure, putting down roots, heading back to being farmers again. Challenges are still there every day, and they always will be. Some of them seem impossible in the moment.

“Do you really want to keep farming?” we ask each other.

And the answer is always, “Hell, yes.”

In 2003, Teresa Retzlaff and her partner, Packy Coleman, began farming on the north Oregon coast. Six years later they managed to purchase land near Astoria, and now live and farm on 46 North Farm in Olney, Oregon, where they’re building both their soil and a very big elk fence.

“Excerpted from Greenhorns: 50 Dispatches from the New Farmers’ Movement (c) Zoe Ida Bradbury, Severing von Tscharner Fleming, and Paula Manalo. Used with permission of Storey Publishing.”

Over at HOMEGROWN.org, we asked folks to tell us their best “How Not To…” story — check them out! And add your own “How Not To” story here!