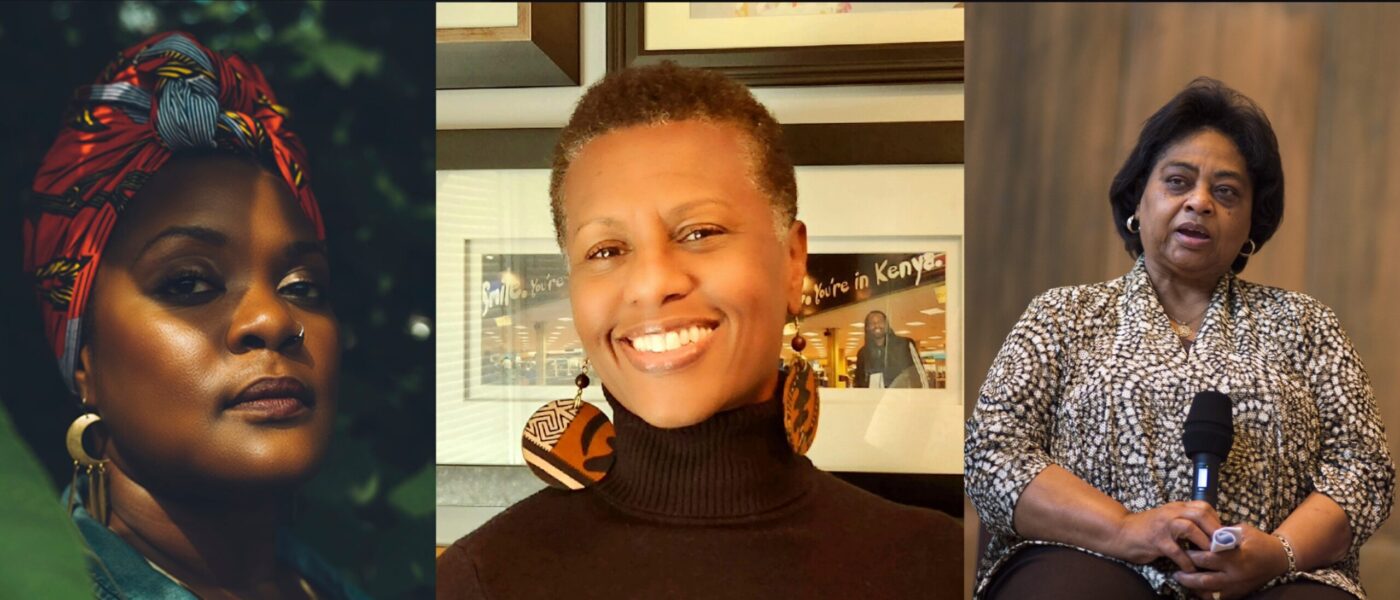

How do farmers lose land? As Kenya Crumel of the National Black Food and Justice Alliance says, it’s not like losing a set of keys: “Nobody’s just accidentally losing land.” Rather, she explains land has been taken – specifically from Black farmers – through a variety of means over the last century. The decline is staggering! In the 1920s Black farmers held somewhere between 15 and 19 million acres of land and represented 14% of all American farmers. Today, Black farmers represent 1% of all American farmers and own as little as 2 million acres of land. In this episode of Against the Grain, we hear from Kenya, Shirley Sherrod of the Southwest Georgia Project, and from Farm Aid artist Kyshona, about their experiences with land, legacy and farming. You’ll learn how farmers and organizers are fighting back to both defend and reclaim farmland and, of course, you’ll enjoy some musical performances from the Farm Aid archives.

Listen to episode three below, and make sure to subscribe in your podcast app of choice!

Kyshona

Kyshona is an artist ignited by untold stories, and the capacity of those stories to thread connection in every community. With the background of a licensed music therapist, the curiosity of a writer, the resolve of an activist, and the voice of a singer – Kyshona is unrelenting in her pursuit for the healing power of song.

Kyshona blends roots, rock, R&B, and folk with lyrical prowess. She is both a sought after collaborative vocalist working with artists like Margo Price whom she accompanied on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, Adia Victoria who features Kyshona, Price and Jason Isbell in her single “You Was Born to Die”, and a burgeoning performer in her own right whose 2020 release Listen, was voted Best Protest Album of 2020 by Nashville Scene.

Kyshona’s non-profit organization Your Song offers songwriting for youth empowerment programs, detention, re-entry, recovery, mental health, and veterans centers and organizations.

Kenya Crumel

Kenya Crumel is the Director of the Black Land and Power (BLP) initiative at the National Black Food & Justice Alliance, a coalition of organizations working together to build institutions focused on food sovereignty & land justice. The primary BLP project is the establishment and growth of the Resource Commons, a combination of a non-extractive fund and a national network of Black land trusts that are being established for the benefit of Black farmers. Prior to joining the Alliance in January 2021, Ms. Crumel spent twenty-five years working in the community development field implementing and managing programs that build the capacity of community-based organizations creating economic and workforce development opportunities.

Shirley Sherrod

Shirley Sherrod is a nationally-recognized, longtime civil rights activist and advocate for family farmers. Mrs. Sherrod is the former Georgia State Director of Rural Development for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Currently she serves as Executive Director of the Southwest Georgia Project, a social justice organization she and her late husband, Charles Sherrod, founded to combat persistent challenges in their region. The Sherrods lost their farmland when the USDA denied their loans, and so they joined the Pigford v. Glickman class action lawsuit.

Watch Kyshona with The Black Opry performing “The Echo” at Farm Aid 2023 in Noblesville, Indiana.

In this video, Allison Russell performs “Requiem” with Kyshona and Lukas Nelson at Farm Aid 2023 in Noblesville, Indiana.

Hear Shirley Sherrod talk about her fight for Civil Rights and farmers in this audio slideshow.

Click here to watch The Black Opry’s entire Farm Aid 2023 set with Kyshona

AGAINST THE GRAIN EPISODE 3: Nobody’s Just Accidentally Losing Land

KURN: Patagonia Workwear built for the ones who don’t wait around, the ones who prove that it’s possible to make a good living on a living planet.

KURN: Welcome back to another episode of Against the Grain, The Farm Aid podcast that brings conversations from farmers, organizers and artists to your ears. Just like we do at our annual festival. I’m Jessica Ilyse Kurn

FOLEY: And I’m Michael Stewart Foley. Jess, You know what I’ve been thinking about as we prepare for this episode?

KURN: No, I don’t know, but I have a feeling you’re gonna tell me.

FOLEY: Yes. Thank you for indulging me. Do you remember that interview we did with Kyshona at our 2023 festival in Indiana?

KURN: Yeah, of course. How could I forget she’s kind of a breakout star playing with the Black Opry and Farm Aid Board artist Margo Price last year; and just this year touring with Allison Russell. She’s such an amazing singer songwriter and storyteller. Yeah.

FOLEY: And she played such a powerful set that day in Indiana alongside Black Opry artists, Tylar Bryant and Lori Rayne.

KURN: Side note, their entire Farm Aid 2023 set will be linked on our show web page.

FOLEY: Glad you remember to plug that. So back to why I was thinking about that interview with Kyshona. She told us about her interest in who owns the land and how her own family’s experience as Black farmers mirrors that of so many who’ve lost their land.

KURN: And she’s doing some serious detective work in Washington DC with a genealogist at the National Museum of African American History and Culture to trace the history of her family’s land ownership here. Take a listen to Kyshona backstage at this year’s festival in Indiana.

KYSHONA: A lot of farmers are working with legacy. This was the perfect timing for me to be invited here when I’m so focused on legacy land ownership, you know, so you can, you know, connect with the genealogist, they help you track down your family’s history. So through this, I understood like how to look at deeds, right? And so I’m looking back at the deeds of the land that my grandparents land sits on right now and seeing that it used to be 100 plus acres, 175 acres. So for me, I’m trying to figure out how did the Black man in South Carolina have 100 and 75 acres? And how are we left with only two?

Right? And so it’s been this question of um tracing the paperwork following the money, looking at the names, knowing that the land meant so much to my grandmother, my great grandma, my great aunt, I mean, they had farms knowing also that like I had a great, great, great grandmother, Margaret who bought land as a formerly enslaved woman for a donkey and a buggy. You know what I mean? And just what she must have gone through to acquire that and sign her x on the line in order to acquire this land and thinking that we only have two acres of some of that land left back, you know, where it’s overgrown. So I’m still in the the process of exploring and understanding my own family’s legacy and title to land. But it’s if anything, I want to hold on to the land even more and trying to find ways of using that land to bring back some kind of prosperity to the community that my mother grew up in, which is now kind of desolate.

FOLEY: Pretty incredible, right? Maybe not all listeners know this, but Farm Aid has since its founding in the 1980s, partnered with a number of organizations in an effort to prevent what’s conventionally called Black land loss, though it really ought to be called land theft.

KURN: That’s right. And we’ll learn land theft can take a variety of forms. Kyshona’s experience of her family losing more than 100 acres of land brings this to light. That’s why we want to introduce the topic of Black land loss in this episode and figure out what happened.

FOLEY: So we’ll hear from Kenya Crumel of the National Black Food and Justice Alliance, Miss Shirley Sherrod of the Southwest Georgia Project and formerly of the United States Department of Agriculture, otherwise known as the USDA, as well as more from Kyshona.

KURN: And here she is playing on the Farm Aid 2023 stage.

KYSHONA: My name is Kyshona. I’m originally from South Carolina. I come from a family of domestic workers, formerly enslaved people. We understand how important land is to us This is called the Echo.

[Kyshona at Farm Aid 2023]

FOLEY: And just a quick word to say. Thanks to our founding sponsor Patagonia Workwear. Built for the ones who don’t wait around the ones who prove that it’s possible to make a good living on a living planet.

KURN: Welcome back. This is the story of land lost, but definitely not forgotten and is one of the driving forces behind Kenya Crumel’s work. She’s the director of the Black Land and Power Initiative at the National Black Food and Justice Alliance.

CRUMEL: We’re a coalition of 56 Black led food and land based organizations, organizing and building institutions and amplifying the hard work that’s being done to actualize self-determination and land justice and uh liberation for Black farmers and land stewards.

KURN: It would be great to start if you could break that down for us and explain Black land loss and kind of the history of how we got to the point.

CRUMEL: First of all the term land loss we joke about because, you know, we lose things like our keys and our wallet and our phone, right? Like nobody’s just accidentally losing land. I’ll bring it to the Civil War, post Civil War reconstruction era after, you know, enduring brutal enslavement. Black leaders gathered in Savannah, Georgia. And, and when asked about what they would need to start this new life of freedom. They said land. Many people have heard of 40 acres and a mule that was um a field order by General Sherman that promised 400,000 acres in total to newly freed enslaved people.

Of course, President Andrew Johnson rescinded on that promise. However, despite all the tricks and false promises and exploitation, Black people in this country were able during that reconstruction era to work and save enough money to purchase between 15 to 19 million acres of land that was between 1910 and 1920 the height. And we’ve never achieved that. We’ve never had that much land ever since. And so we went from 15 to 19 million acres to 2 million acres in less than 100 years.

KURN: Along with that peak of Black owned land in 1920. The number of Black farmers also topped out at nearly 1 million or 14% of all farmers during the so-called roaring twenties. As of the last census of agriculture, that number has fallen steeply and hovers around 45,000 Black farmers representing only 1% of all farmers today.

FOLEY: Could you talk a little bit more about all of the various mechanisms that were responsible for that dramatic theft, right? Not loss of land since the 1920s. Because I imagine it’s legal, economic, political, cultural, there’s a lot of factors involved.

CRUMEL: There are myriad reasons that Black people have been robbed of their land. Um We can start with domestic terrorism. KKK, right? People have been terrorized and run off of their land, houses burned, et cetera. Uh There’s eminent domain uh that often happens in poor communities where you know, the local government will say, well, we need this land for the community and, and Black people are just shuffled, pushed off to another area. There were a number of communities that you may be familiar with, such as uh Tulsa, Oklahoma or Rosewood, Florida that were burned, thriving Black communities burned to the ground.

Lake Lanier in Georgia. That was a Black community that is now a Lake Martin. Central Park in New York City used to be Seneca Village that was a Black community. So, so all these Black communities that um when I guess when it was discovered that there, this was ideal for a location for something else, some capitalist reason. OK. Well, y’all gotta go now and if you either you go willingly or we, we just go, you know, we will remove you.

And then of course, there’s the USDA um and a variety of policies that have contributed to people not being able to hold on to their land or sort of being tricked out of their land. So, for example, um you know, applying for a loan at the beginning of growing season or prior to growing season, even beginning, say you ask for, I don’t know, $50,000, but you are awarded $20,000 and you don’t even get the money till September. The time for planting is gone. So how are you going to yield a crop that’s gonna be able to allow you to pay back your loan? So, you know, it’s just this, this vicious cycle. So, I mean, we can go down throughout history, but it’s to this day that that people are threatened by, you know, by a variety of means.

FOLEY: Yeah, this is a great example of the nuanced varied ways that land has been lost or taken from Black farmers, the USDA, of course, which is supposed to be helping all farmers, in fact, consistently played a role in the decrease in Black agricultural land ownership since the 1920s.

KURN: Shirley Sherrod is a good example and she paints this picture for us. She is a storied advocate for farmers from the time in the Civil Rights Movement and is perhaps best known for her decades long work with the Southwest Georgia project, which she currently heads today. This organization was founded to empower communities through grassroots organizing around food farming and human rights.

SHERROD: My name is Shirley Sherrod and I grew up on the farm in Baker County, Georgia. And uh I had no intention of actually being a part of any farming operation or any farm work. But during my senior year of high school, my father was murdered by a white farmer. My father and others were meeting secretly to start the Civil Rights Movement. Now, I don’t know whether that’s the reason why he was murdered by this farmer or not. But this farmer, he had an adjourning farm and some of his cows had actually gotten into our pasture.

And we met him the day before he murdered my father on the road as we were going to church and he said he was coming for the cow the next day when they gathered at the uh pasture, the white farmer tried to claim other cows in our pasture. He and my father argued. My father told him we don’t have to continue this. We can just go to court and um he shot him. The grand jury which was a local white grand jury refused to indict him. So nothing was ever done. I made the decision to stay in the South and devote my life to working for change. So, uh I started initially with the Civil Rights Movement in the rural area. And that means working with people who lived and worked and owned farms.

FOLEY: Shirley Sherrod has always been a fierce advocate for farmers. If you want more information on her and her amazing work, go to our website to learn more.

KURN: Yeah. She channeled this really terrible tragedy into a decades long career to advocate for fairness, justice and equality for farmers.

SHERROD: My father would be so proud of the work that I’ve done through the years. I think of him often and that’s what drove me so much to help other farmers. One farmer had called me. He received a letter saying, um, they had given him an appointment to come into the office. So this farmer called and asked if I would go with him. The county supervisor started telling the farmer that he would be foreclosing on the farm.

He’s just going on and on and he’s quoting regulation. That was, you know, he was totally off base with it. It was all regulation and we had no regulation. So I stopped him and I said, will you put that in writing? Now, see, I think he probably knew he was not saying the right thing, but he would have gotten by with that if I hadn’t been there knowing that what he was saying was not the current regulation. He said, I ain’t put nothing in writing.

And then each time he made a decision, we would appeal after quite some time working on it, it ended. And that farmer has the farm, that family, they have the farm today when I even ride through some of the area in Southwest Georgia now and can point to a farm and say, you know, I have to say that farm, that’s such a good feeling, knowing that the system tried to take them out and we worked so hard to keep them there.

KURN: Wow. I’m really letting her story sink in. It’s so powerful and the way she tells it too. And this was far from the only time Shirley Sherrod personally faced injustice or helped a farmer navigate discrimination in the USDA system. And then eventually in 2009, President Obama tapped her to work for the USDA as the Georgia State Director of Rural Development where she continued to help farmers within the belly of the beast.

FOLEY: Yeah, if she wasn’t there, that farmer she mentioned would have easily lost his farm. Not an uncommon story which has led to a deep distrust of the USDA among Black farmers. We’ll cover more of them when we do a full season on Black land loss and discrimination

KURN: In that season, we’ll also dive into the Pigford vs. Glickman case, which Shirley Sherrod was a part of. This case was a class action lawsuit against the USDA for discrimination and is one of the largest civil rights settlements in US history. So stay tuned. For all of that and more.

FOLEY: Digesting Shirley Sherrod’s story, it’s easy to see why Kenya Crummel of the National Black Food and Justice Alliance kept coming back to the point about the deep distrust of the government and particularly the USDA within the Black farming community.

CRUMEL: So there’s a lot of trauma. It’s real. I know that people want to believe: that was then, but there’s a lot of people that just associate land and farming with slavery and sharecropping and it’s understandable. But you know, we’re uh from the time we’re little indoctrinated with these awful images of all the things that Black people in this country endured. Um So it’s understandable that there’s trauma.

That’s why education about the history and empowering people with political education just um and supporting people in their efforts to have their land based ventures be successful is critical.

KURN: Kenya’s organization is doing just that, working to build trust and rebuild lost agricultural knowledge. Ultimately, the alliance hopes to reclaim land and bolster training programs to get more Black farmers on that land.

CRUMEL: What we’re working towards is putting 15 million acres of land into trust for the exclusive benefit of Black farmers. The National Black Food and Justice Alliance uses that number that 15 million acres as our North Star.

FOLEY: So the alliance plans to do this in a couple of ways, one of which is to keep a finger on the pulse on the movement of land in farm country and purchase it when it becomes available for their Black land trust.

CRUMEL: When we see that land is available, we purchase it if it meets the qualifications that we’re looking for in terms of potential land for growing. And if it’s an environment where we feel safe purchasing that and putting it into trust. We want to form collectives or invite existing collectives to steward that land. Anything that we put into trust would not be for individual quote, unquote ownership, this would be for collective stewardship.

KURN: This plan will take a lot of effort, money and patience, but it’s inspiring to think of affording people access to land when their families previously had it stripped away. Not to mention adding a slew of new Black farmers.

FOLEY: Yet knowing that we barely touched the service on this large topic we’re gonna end here.

KURN: You’re just gonna have to stick around for the full season.

FOLEY: Another nice plug.

KURN: Well, for now, we’ll circle back to Kyshona live on the Farm Aid 2023 stage where she performed Requiem with recent Grammy Award winner, Allison Russell and Lucas Nelson.

FOLEY: Visit our website to find a great audio slideshow that combines photos and stories from Shirley Sherrod’s life as well as Kyshona’s Full Farm Aid 2023 performance and more. Visit www.farmaid.org/podcast

KURN: If you have questions thoughts or ideas for us. We’re always happy to hear from you. So please find our email address on our website. And don’t forget you can also engage with us on Farm Aid social media. Just look for at Farm Aid on Instagram, Facebook or X/Twitter. And don’t forget you can also go to our Youtube channel where we have almost 40 years of all of our festival footage.

KURN: Against the Grain was written and produced by us with sound editing by Blurry Cowboy Media. Shirley Sherrod’s interview was recorded in a StoryCorps booth, and our theme music was written and performed by Micah Nelson.

FOLEY: Thanks so much to Kyshona, Kenya Crummel and Shirley Sherrod. There’s so much more to each of these incredible women than we could tell you. Be sure to visit our website to learn more about each of them and find links to their current projects. Thanks so much for listening.

KURN: And a huge thank you to all the farmers out there. We’ll chat with you next time.

FOLEY: Patagonia Workwear, durable, timeless gear built for the ones who prove that food production, skilled trades, construction, and ecosystem restoration can and should cause the least amount of harm Patagonia Workwear believes that it’s possible to make a good living on a living planet.

Special thanks to our founding partner, Patagonia Workwear.

Photo Gallery

Next

Factory Farms