June 2021 Update:

The developer behind the Keystone XL pipeline has officially canceled the project. Read the 2015 post below to see context for why farmers, activists and Farm Aid board member Neil Young came together in Washington, D.C. to oppose the pipeline.

Dear Farm Aid,

Here in the West, farmers have often fought energy companies who want to use their land for mining and oil extraction. As I watch my neighbors rally to save their land, I can’t help but wonder why we’re considering putting farmers and our farmland at risk with things like the Keystone XL Pipeline.

Gold never rusts,

Rob G.

As stewards of the land, farmers and ranchers are often the first to see threats to the health of our land and water. Time and again, issues that achieve lightning rod status in the public eye start years earlier for the people on the ground: family farmers. Farm Aid has long supported farmers and ranchers, and the organizations they lead, in their efforts to protect their land and property rights from corporations seeking to extract energy for profit.

“Change is coming. Why not stand up and put America on the right side of history? We need to end the age of fossil fuels and move on to something better.” — Neil Young

The Keystone XL Pipeline is just the latest example, and has resulted in an inspiring display of people power. In April, a group of farmers, ranchers and tribal communities called the Cowboy Indian Alliance marched into Washington, D.C. (on foot and on horseback!) to set up an encampment of tipis on the National Mall to protest the proposed Keystone XL pipeline. The five-day Reject + Project event brought together critical voices from communities who live at ground zero for the controversial project, especially the people who steward our land. Farm Aid board member Neil Young attended to offer his voice in support of their efforts and Farm Aid issued Farmer Leadership Grants to offset travel expenses so that Nebraska farmers and ranchers could attend the event and speak their truth.

Why would farmers and ranchers care about the Keystone XL pipeline? Why would Farm Aid stand by these farmers and ranchers in their efforts? And how does the pipeline impact the people who grow our food?

A tale as old as time

Like any complicated issue, some context is helpful. So let’s start at the very beginning.

The introduction of extractive industries into rural areas is nothing new. Almost since the beginning of U.S. westward expansion, mining, drilling and related activities have caused “boom and bust” cycles in small towns. Landowners, including farmers and ranchers, have continually fought for basic rights in the face of energy development, like holding an energy company accountable for environmental or property damages they cause, or receiving due notice before the company can come onto their land and drill. In addition, landowners often face eminent domain if they don’t agree to sell their land.

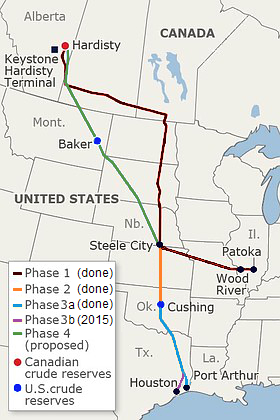

In this case, TransCanada, a Canadian energy company, has proposed an extension to its Keystone Pipeline called the Keystone XL. The hugely controversial 1,179 mile-long pipeline would bring tar sands oil from Canada, across the U.S. border, to refineries in the Gulf Coast. Keystone XL represents the final phase of TransCanada’s $13 billion, 3,800-mile pipeline system. Because it crosses international borders, a Presidential Permit is required to green-light the pipeline’s construction. Though the pipeline was on the fast track for approval, the people living on and working the land turned this into a fight that’s gone on for five years and counting.

The first speed bump was the Sand Hills region of Nebraska, a unique and fragile ecosystem of shifting sands and wetlands, which the proposed pipeline was supposed to cross. After a successful battle to protect the Sand Hills, TransCanada was forced to reroute. And that’s where they hit a roadblock. Some landowners along the new route refused to sell their land to TransCanada, and the company retaliated by threatening to take it through eminent domain, whereby the government or a third party can “justly” pay to take private property if it will be used for public benefit or in the public interest. In the ensuing legal battle, a Nebraska court ruled it unconstitutional for a private foreign company to take individual’s property via eminent domain. As a result, the Keystone XL remains unapproved.

Wizipan Little Elk, of the Rosebud Sioux, and Art Tanderup risk arrest by standing in the Washington Monument Reflecting Pool in D.C. to protest TransCanada’s proposed Keystone XL pipeline. (Photo by Garth Lenz / iLCP)

A leaky proposition

The Keystone XL starts in western Canada’s Alberta province, where one of the world’s largest deposits of tar sands sits. Tar sands aren’t like other sources of oil and converting the extracted bitumen (a heavy, tar-like substance) into a usable form is incredibly energy and water-intensive.

Already, bitumen extraction has significantly degraded Canada’s forests and created vast stretches of waste ponds linked to river contamination. Combined with their notable greenhouse gas contributions, this earns tar sands a low grade on the environmental front. The U.S. State Department reports that by the time tar sands oil is burned in a car, it creates 17 percent more carbon emissions than crude oil refined in the U.S.[1]

Extending from its source in Canada, the Keystone XL’s path would cross the border in Montana and cut across South Dakota and Nebraska before joining the existing pipeline in Steele City, Kansas. The proposed path crosses some of America’s wildest lands and ecosystems, and also covers a wide swath of fertile farmland and the West’s major agricultural water source: the Ogallala Aquifer. The Ogallala is what makes farming possible in the Great Plains, and also provides drinking water for 2.3 million people in communities across several states.

Worried landowners and activists maintain that more study is needed on the particular risks of tar sands (for example, some suggest tar sands oil may be particularly corrosive to pipelines, increasing the likelihood of leaks) and the Ogallala’s geography. They ask for proper emergency response plans and due attention to the rural communities who bear the brunt of the risk.

Concerns that pipeline leaks and spills will damage unique and valuable natural resources are not unfounded. The original Keystone pipeline suffered over a dozen leaks in its first year (2010), including a devastating spill that shot a geyser of some 500 barrels of oil 60 feet into the air. Over 20,000 gallons were spilled over precious North Dakota soil in just one hour. Years later, families throughout the Midwest and Plains are still recovering from tar sands spills in their communities, not to mention the persistent health and environmental impacts the people of the First Nations in the Canadian tar sands zone endure.

At Farm Aid, we’ve heard directly from family farmers whose farms lie in the proposed path of the Keystone XL Pipeline. Many of these farms have been in the same family for generations. Now the Keystone XL Pipeline jeopardizes the health and viability of that land, rather than ensuring its health for future generations.

This has turned many farmers and ranchers into activists, such as this month’s Farmer Hero Art Tanderup who attended the Reject + Protect rally. Art and his fellow family farmers and ranchers sacrificed precious time during the planting season to protest the pipeline because they work the land every day and know its needs and vulnerabilities. They know the benefits the land brings to all of us when it is cared for and they know what’s at stake when it is not.

Follow the money

Of course, Rob, your question asked why this is even being considered. And that leads us to ask, who benefits? And at what cost to the rest of us?

Despite its hefty environmental impact and the great risk of irreparable damage to water resources, private property and farm and ranch businesses, tar sands extraction is still considered a necessary endeavor in a world of rapidly dwindling fossil fuel stocks. Certainly, it is a lucrative one for some. For TransCanada and the fossil fuel industry, the Keystone XL pipeline means more business and higher profits. Though there is the potential for the pipeline to create jobs, studies have found that this will mostly be on a short-term basis. Whether it results in long-term economic development is heavily debated.[2]

At a time where we are losing farmland and farmers every single day, and during a time of extreme drought that already threatens agriculture in the U.S., the bottom line is that the profits of private companies shouldn’t come at the expense of family farmers and ranchers, Native American communities or rural residents who do and will continue to feel the brunt of the impact from fossil fuel extraction. As Neil Young says, “We need to move onto something better.”

Neil Young and Art Tanderup stand up for the land in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Bold Nebraska)

The path forward

The U.S. needs a comprehensive energy policy that supports a diversity of homegrown energy alternatives that generate enduring jobs, benefit rural communities and protect our precious environmental resources now and into the future. Family farmers and ranchers are part of the solution and are integral to establishing America’s clean energy future. The Keystone XL pipeline is not.

The end of this tale remains unclear. The Obama Administration recently announced that it would delay a final decision on Keystone XL because of the lack of an approved route for the pipeline through Nebraska and is unlikely to make a final decision until after mid-term elections in November. What is clear, however, is that the power of everyday people who come together to speak their truth can turn the tide of history.

Sources

1. U.S. State Department. (2013). Draft Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement for Keystone XL Pipeline Project. http://keystonepipeline-xl.state.gov/draftseis/index.htm

2. Bell, Alistair. Beyond the hype, Keystone would yield few permanent jobs. March 14, 2014.http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/14/us-usa-keystone-insight-idUSBREA2D08620140314