Homegrown Stories is a storytelling project from our partners at Western Organization of Resource Councils (WORC). It celebrates the hardworking people in our food system trying to do things right. The people of these stories are hard at work to create diverse, wholesome, regional food systems in our communities. They feature people working hard to keep the land healthy and their communities nourished.

WORC gave us permission to repost these farmers’ Homegrown Stories here in an effort to change the narrative of agriculture in America.

Ernest Weston: Being A Good Relative

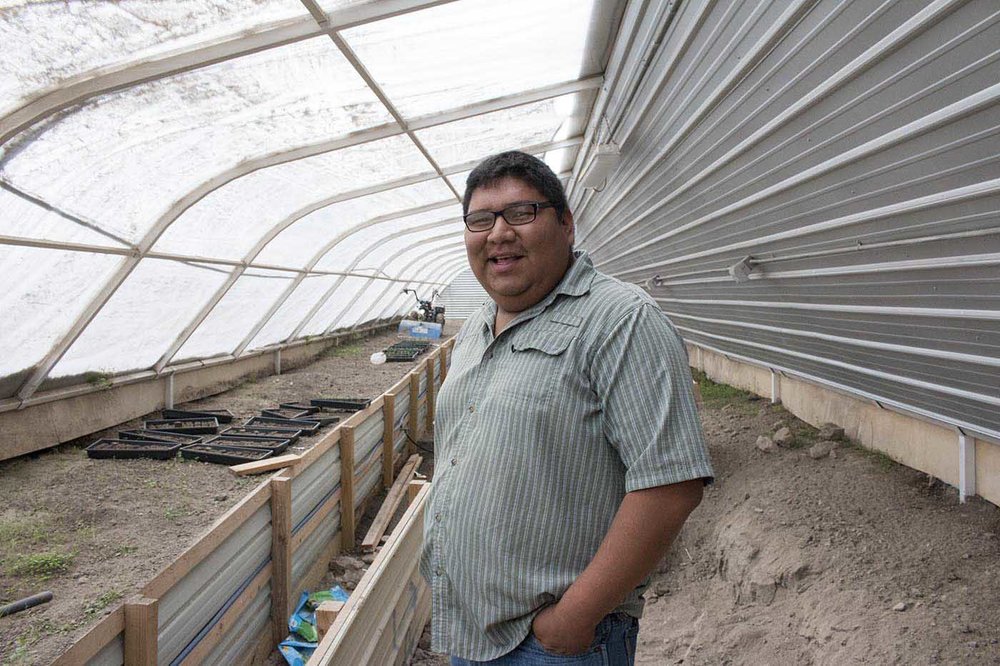

Food Sovereignty Program Coordinator at Thunder Valley, Ernest Weston, stands in a newly built green house on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota

“I remember the morning I left for school. I loaded up the Dodge pickup at 4 a.m. and then went inside to say goodbye to my family. We all cried. We all just stood there hugging and crying,” said 24-year-old Ernest Weston.

Ernest Weston is a member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe. He was born and raised on the Pine Ridge Reservation in the Brotherhood Community on the original allotment his grandparents acquired under the Dawes Act. He is the oldest of six and the first in his family to go to college.

Ernest worked towards a political science degree his first two years at South Dakota State University.

“I wanted to study political science and change policies through a politician’s role,” said Ernest.

That changed when course after course let him down.

“No one talked about tribal issues, and no one wanted to — no one really seemed to care,” said Ernest.

After realizing political science was not the right fit, Ernest switched to sociology his junior year. In 2016, the summer after changing his major, Ernest received a job offer from Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation, a new community development initiative that had just started up a few miles from his home in Brotherhood. Today, Ernest is the Food Sovereignty Program Coordinator at Thunder Valley, the largest community development initiative in Indian Country. Ernest is now finishing his degree in sociology with an emphasis on rural development. He is changing lives in his community from the ground up.

Ernest in the chicken pen at Thunder Valley

Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation is a Lakota-run, grassroots initiative to create systemic change on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The 34-acre development has nine program areas to rebuild the community through housing and home ownership initiative; workforce development; youth leadership; regional equity; community development; Lakota language; social enterprise; arts and culture; and food sovereignty programs. Thunder Valley is giving Pine Ridge the tools to prosper via education in areas that promote self-sufficiency and sustainability.

Raised garden beds at Thunder Valley

Ernest’s position as the Food Sovereignty Program Coordinator fits since he has been involved in food all of his life.

Ernest was raised on a cow-calf operation.

“My Uncle Scott taught me all the parts of ranching,” said Ernest. “He taught me how to rope, brand, fix fence and move cattle, all while I was in grade school.”

Ernest’s family also had huge vegetable gardens which provided the entire family with fresh produce. Ernest remembers his grandpa growing the best blue hubbard squash.

“My grandpa looked after everyone in the community. He always grew more than we needed and would give truckloads away to anyone who was hungry,” said Ernest.

Those values of taking care of one another echo throughout the entire Brotherhood community. It commands one to “be a good relative,” whether, to a neighbor, friend, family member, animal or the earth, you take care of one another.

Thunder Valley

“I grew up being taught the importance of growing your own food and nourishing your community. Growing up with those principles guided me and helped me become who I am today,” said Ernest

When Ernest moved to Brookings for school, he was instantly overwhelmed by how different it was than his home.

“The biggest difference was all of the choices of grocery stores and restaurants with good food,” said Ernest. Food production on Pine Ridge is limited and the food that is produced on the reservation leaves. Ninety-five percent of the commodities produced on Pine Ridge, such as cattle, corn and sunflower, are exported. Pine Ridge is a food desert, meaning the community has very restricted access to produce or healthy food options. Residents of Pine Ridge have to drive 85 miles to find healthy food. Their closest option to fresh fruits and vegetables is located in Rapid City.

Compound that with the fact that most Pine Ridge residents don’t have the means to make a weekly 170-mile round-trip grocery run. Eighty percent of residents on the Pine Ridge Reservation are unemployed; Forty-eight percent live below the poverty line. Inadequate housing makes up most of the homes in the area. Preventable diabetes is at the highest rate in the entire country on the reservation. The average life expectancy on Pine Ridge is 66.8 years, the lowest life expectancy in the entire nation.

Kyle South, Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Reservation

“I think it really hit me just how bad it was on the reservation when I came back home my first break for Thanksgiving,” said Ernest, “I just remember driving through the reservation and thinking ‘holy shit things are bad here.’”

Seeing that stark contrast between his home and Brookings, a city just five hours away, energized Ernest to educate himself in order to help his community. When Ernest was offered the position at Thunder Valley, it seemed like the perfect opportunity to help his community.

“Food sovereignty is being able to feed ourselves.”

As the Food Sovereignty Program Coordinator, Ernest is all in on Thunder Valley’s ag initiatives. He handles everything from policy work to helping the operation thrive, to teaching people on the demonstration farm. To Ernest, food sovereignty is defined as a community’s right to wholesome food and food independence.

“In other words, ‘food sovereignty’ is being able to feed ourselves,” said Ernest.

With the ability to feed themselves, Ernest said Pine Ridge would have new skills to fix other aspects of life on the reservation.

“Health and economics are so tied into our food system. Reclaiming our food system and teaching our people how to provide for themselves with food, along with our other initiatives can reshape Pine Ridge,” he said.

Thunder Valley uses a teaching model.

“We want to be a model for Indian Country to show nations how to be more self-sufficient,” said Ernest.

Construction at Thunder Valley

Thunder Valley’s food sovereignty program has two community gardens, a greenhouse, and an egg operation. Thunder Valley has 413 Rhode Island red hens raised on pasture. The egg operation has an egg washing and packaging station that will one day provide fresh eggs to community members and surrounding areas. As of now, Thunder Valley gives the eggs away to a local food bank.

The South Dakota Department of Agriculture gave Thunder Valley an egg dealers’ license, which allows them to sell their eggs legally. Ultimately, Ernest wants grocery stores and restaurants to carry their eggs. This would provide a profit for training more farmers and also keep reservation food dollars on the reservation. Ernest’s ideal Pine Ridge food system is closed loop in which consumer and producer benefit hand in hand.

“We have come a long way in terms of building the demonstration farm, but we still have a lot of work to do to make it work,” said Ernest. He says some federal, state and tribal policies are standing in the way of their ability to thrive.

For example, recently, the state of South Dakota notified Thunder Valley that the eggs wouldn’t be available for purchase with Special Supplemental Nutrition Program funds for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). The reason? The eggs are brown instead of white. This is a significant blow to a program aimed at helping feed a community where half the residents sit at or below the poverty line.

“Ideally, tribal policy would allow tribal producers to feed their communities and families, keep food within the reservation and make a living on that system,” said Ernest. “If we’re truly a recognized sovereign nation, our own labels and regulations should be respected.”

Chickens roaming at Thunder Valley

Despite the policy setbacks and hurdles, Ernest has never lost sight of his goals for Thunder Valley.

“My personal goal in this position is to implement food sovereignty programs in all of our schools … educating a community really starts with students. We have had some demonstrations and workshops in the schools already, and the administrators are always thankful to have us and want to see more,” said Ernest. “It just feels amazing to be bettering the community I grew up in. Seeing people engage in this work I do and love makes me happy. We still have a long way to go, but I’m hopeful we’ll get there and confident we’re headed in the right direction.”

Construction at Thunder Valley