As Farm Aid board artist Dave Matthews says, “the vast majority of people are good, the vast majority of people are community driven and want to take care of each other,” and understanding that fact can motivate us to change the farm and food systems that prioritize corporate profits over communities. In this second episode of Against the Grain, called “Hoodwinked,” you’ll hear from artists Dave Matthews and Allison Russell, former contract poultry farmer and whistleblower Craig Watts, and organizer Tim Gibbons about the scourge of industrial agriculture that has come to dominate our farm and food systems in recent decades. They’ll explain how this system evolved and propose solutions for how to get out of it. And, of course, you’ll hear some great music from past Farm Aid festivals along the way.

Listen to episode two below, and make sure to subscribe in your podcast app of choice!

Take Action on Corporate Consolidation!

As you heard in episode two, U.S. food production is highly consolidated among just a few large corporations, especially in the meat, dairy, poultry and grain industries. This consolidation has led to high prices for consumers and unfair compensation for producers. Take action by writing to USDA Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack. Let the Biden administration and the USDA know that they must do more to diversify their suppliers and stop perpetuating the dominance that several large corporations have over our food system.

Take Action and learn more here.

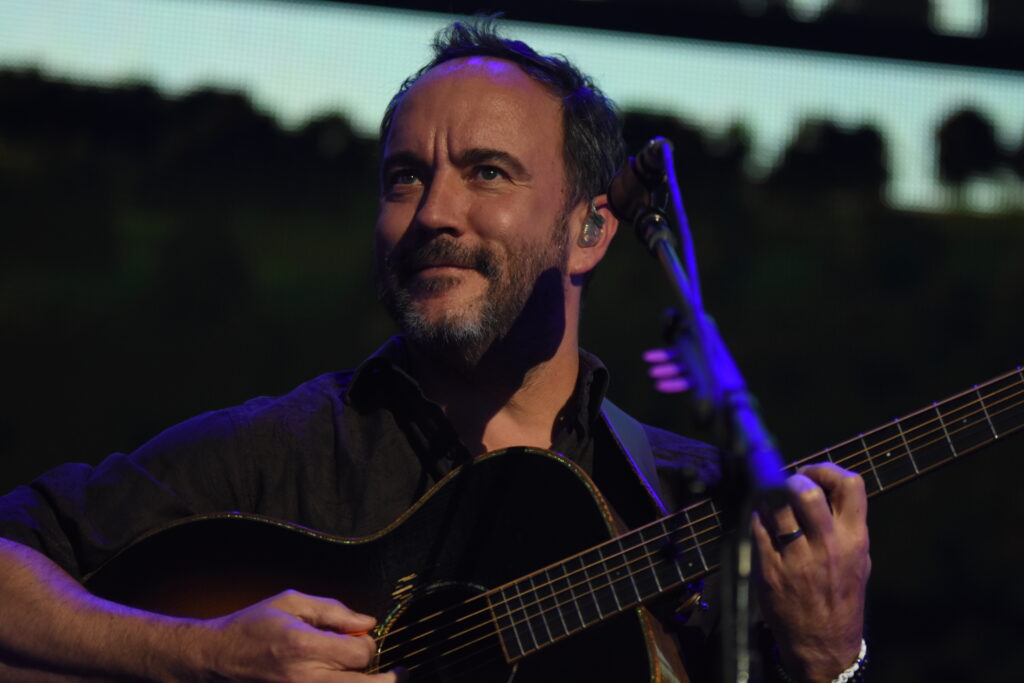

Dave Matthews & Tim Reynolds at Farm Aid 2023. Photo © Brian Bruner / Bruner Photo

Dave Matthews

With a career spanning over 30 years, Dave Matthews Band is one of the most influential bands in rock history. In 1991, vocalist/guitarist Dave Matthews decided to put some songs he had written on tape and sought the assistance of drummer Carter Beauford and saxophonist LeRoi Moore, who were both accomplished jazz musicians in the local Charlottesville, VA music scene. 16-year-old bassist Stefan Lessard came on board shortly thereafter. Their infectious, distinctive sound garnered lots of early attention and a die-hard loyal fan base, catapulting the band into one of the most successful touring acts of the past three decades. The band has sold more than 25 million tickets since its inception, making them the second largest ticket-seller in history.

The band will release their 10th studio album, Walk Around the Moon, May 19, 2023 on RCA Records. To-date, their nine studio albums and numerous live recordings, have sold a collective 38 million CDs and DVDs since the 1994 release of its major label debut, Under the Table and Dreaming. The GRAMMY®-winning band’s many hits include “What Would You Say,” “Crash Into Me,” “Too Much,” “Everyday,” “American Baby,” “Funny The Way It Is,” “Mercy” and “Samurai Cop (Oh Joy Begin).” The latest single from the new album “Madman’s Eyes” was released January 24, 2023.

The group’s Bama Works Fund, established in 1999, has raised more than $65 million dollars for humanitarian and environmental initiatives. Dave Matthews’ ongoing partnership with The Nature Conservancy has resulted in three million trees being planted since 2020. The continued partnership will bring the total to four million trees in 2023. Named as a UN Environment Goodwill Ambassador in 2019, Dave Matthews Band has a long history of reducing their environmental footprint, going back to their first shows in 1991.

Allison Russell at Farm Aid 2023. Photo © Sharon Carone

Allison Russell

Since the release of her first solo album two years ago, the self-taught singer, songwriter, poet, activist, and multi-instrumentalist Allison Russell has redefined what artistry means in the 21st century. Outside Child, her often devastating, deeply moving, cathartic celebration of survivor’s joy, has become one of the most acclaimed albums of the past 10 years⎯(various honors include three GRAMMY Award nominations, the Juno Award for Contemporary Roots Album of the Year, the 2022 Americana Music Association’s Album of the Year Award, two International Folk Music Awards, three Canadian Folk Music Awards, and four UK Americana Music Awards).

The Returner, Russell’s sophomore album, is a body-shaking, mind-expanding, soulful expression of Black liberation, Black love, of Black self-respect. This new album doesn’t just deliver on the massive promise of the last two years, it brilliantly exceeds all reasonable (and unreasonable) expectations and affirms Allison Russell’s place among music’s most vital artists⎯and The Returner as one of 2023’s most essential recordings. Alongside the Rainbow Coalition Band – a talented ensemble of BIack and POC, queer, and historically marginalized musicians from across the U.S. – Russell uses the power of music in order to spread her message of the “Beloved Community” and is dedicated to lifting others upwards as her own star climbs higher.

Craig Watts

Craig is a former contract chicken grower for poultry giant Perdue. He made headlines when he teamed up with Compassion in World Farming USA to expose animal issues rampant throughout the company’s operations. Craig’s story has been featured in the New York Times and on Tonight with John Oliver. He has been outspoken about the power of giant meat companies, giving testimony on Capitol Hill and sharing his story on the Farm Aid stage with musicians Dave Matthews, John Mellencamp, Neil Young, and Willie Nelson. Craig has received the “2022 Spirit of Farm Aid” award and was named Whistleblower Insider’s “2015 Whistleblower of the Year.

Tim Gibbons

Tim Gibbons has been with the Missouri Rural Crisis Center (MRCC) since 2005. MRCC represents independent family farmers, rural families and their communities and citizens concerned with our food supply, our natural resources and democracy. Tim works to organize a large membership base of farm families, rural citizens and other Missourians to challenge the industrialization and corporate control of agriculture and our democratic process. Through MRCC, thousands of rural Missourians have been empowered by increased opportunities to participate in public policy formation and advocate for Missouri independent family farms and rural communities. MRCC’s mission is to preserve family farms, promote stewardship of the land and environmental integrity and strive for economic and social justice by building unity and mutual understanding among diverse groups, both rural and urban.

Check out this segment from Last Week Tonight with John Oliver covering American poultry farmers and the abuse they endure at the hands of big poultry companies.

Willie Nelson & Family perform On the Road Again at Farm Aid 2016 at Jiffy Lube Live in Bristow, Virginia, on September 17.

Dave Matthews & Tim Reynolds perform “Don’t Drink the Water” at Farm Aid 2022 in Raleigh, NC, at Coastal Credit Union Music Park at Walnut Creek, on September 24.

Allison Russell performs “Georgia Rise” with Margo Price, Sheryl Crow, and Brittney Spencer at Farm Aid 2022 in Raleigh, NC, at Coastal Credit Union Music Park at Walnut Creek, on September 24.

AGAINST THE GRAIN EPISODE 2: HOODWINKED

KURN: Patagonia Workwear built for the ones who don’t wait around, the ones who prove that it’s possible to make a good living on a living planet.

FOLEY: Welcome back to another episode of Against the Green, the Farm Aid podcast where we aim to give you a deeper understanding of our agricultural landscape while also celebrating family farmers the way we do at our annual Farm Aid Festival. I’m Michael Stewart Foley.

KURN: And I’m Jessica Ilyse Kurn. Michael: How have you been?

FOLEY: Pretty good, though I’ve got Dave Matthews’ “Don’t Drink the Water” stuck in my head, which is a little weird. Don’t get me wrong: I think it’s a great song, but it’s also kind of depressing. It’s clearly a song about colonialism – about the powerful, pushing other people off of their land. But, then, that’s also relevant to what we’re talking about this week.

Dave Matthews singing: And I live with my justice/ And I live with my greedy need/ Or I live with no mercy/ And I live with my frenzied feeding/ I live with my hatred/ And I live with my jealousy/ Or I live with the notion/ That I don’t need anyone but me/ Don’t drink the water/ Don’t drink the water/ There’s blood in the water/ Don’t drink the water

KURN: After talking with Dave at this past Farm Aid Festival, this song seems to track with his overall views about greed, particularly corporate greed.

FOLEY: Yeah, it was great to chat with him backstage. It was a little bit noisy, but we had some great interviews back there and got some great content and he was really good because he got into corporate greed when you asked him about politics.

KURN: So, one of the things we’re talking about with a lot of artists is if you would consider yourself a political artist.

MATTHEWS: I mean, maybe everyone says this, but I don’t know that anything isn’t political, you know? I think any action or lack of action is a political act. So I think to not be informed, um, or to be ill informed is a political act, I just, I feel very, I’m very honored to be here and to be part of the Farm Aid family and to sort of raise a voice for farmers who, although we all need them, don’t often have a voice that’s loud enough to be heard. And, you know, and true farmers not where…what they call conventional farming now is, it’s unfortunate that it’s called that, like we say, that’s the norm – is the sort of toxic profit driven farming. And, and that’s part of what, you know, I think Farm Aid is fighting against because that’s really what has done more damage than anything else to the family farmers and to the land and to the environment is this toxic method of farming. And the lie that it’s the only way to move forward. It’s, the only way not to move forward.

KURN : That strong statement from board member Dave Matthews really nailed one of the issues that we want to cover in Against the Grain: The toll that corporate agriculture has had and continues to have on our farmers, our environment and our country in general. Dave almost describes it as a disease that we have allowed to fester.

MATTHEWS: I do think it is foundational. The mistreatment of farm farmers that this country allows and almost endorses on a political level is, you know, is shameful, and we need to do all we can to turn that around so that – not only for the family farmers, but for all of us and for the health of the planet. If there’s something I’m against, it’s this sort of, the idea that a world that’s devoted primarily to profit and primarily to paying its shareholders. And the strange part of it is, you know, I’m sure there’s lots of shareholders of companies that – whether they’re oil companies or they’re, you know, the giant farming corporations – I’m sure those shareholders know that the model isn’t right, but there’s no off-ramp in that model. The corporate model is one that is driven only by profits. So costs have to go down and profits have to go up and there has to be growth. We don’t eat profits, we eat food.

FOLEY: I really appreciate Dave’s assessment of the industrial corporate agriculture model that dominates our farm and food systems. But the question I kept asking myself as he was speaking was how the hell did we get into this mess?

KURN: And what is it like for farmers stuck in these corporate contracts?

FOLEY: Yeah, exactly. So, stick around and hear what we found out.

And just a quick word to say thanks to our founding sponsor Patagonia Workwear: Built for the ones who don’t wait around, the ones who prove that it’s possible to make a good living on a living planet.

Welcome back to Against the Grain. Jessica, you’ve been traveling recently, right? Remind me, where were you?

KURN: Good memory. I took a road trip to Chicago, which was lovely. And actually along the way, I thought long and hard about agriculture. Wait, let’s get some road music

[Willie Nelson “On the Road Again” from Farm Aid 2016]FOLEY: Nice music choice! I also love it that when you’re driving the highways of America, you’re thinking long and hard about agriculture and of course, working for Farm Aid, I do that too. But my kids give me a really hard time because I’m constantly talking to them about birds of prey that I spot on the highways.

KURN: Hazards of the job, I guess! If you’ve never been Chicago is magnificent. A truly sparkling metropolis with tall buildings and millions of people scattering this way and that and then as I drove east on I 90 I passed into Indiana. This was just as the sun was starting to set. And the interstate took me along rural farm country. I passed idyllic looking farms that were illuminated by the setting sun and honestly, it does sound cliche and I know that as the song goes, it’s supposed to be grain, but the rows of corn were almost amber and then…. right around the exit for Shipshawana Indiana, I passed along these long narrow buildings, row after row of them.

FOLEY: Ah, I know where this is going. Were they CAFOs?

KURN: Yep, Confined Animal Feeding Operations, which on their face may not seem too bad, but once you take a closer look and breathe it in, things are not quite as they seem. Those beautiful rolling hills were spotted with these sterile buildings containing thousands upon thousands of animals raised in confinement, and this particular area, it’s mostly chickens.

FOLEY: Right, CAFOs have been on the rise for decades, basically since the 1980s and 90s when Farm Aid was brand new. As Americans continue to increase our meat consumption, fewer and fewer farms produce that meat because the industry has been steadily scaling up to crush competition and maximize profits.

KURN: And I’ll note the poultry industry has changed to support our growing consumption of chicken. We’re at the point right now where the average American consumes about 90 lbs. of chicken a year. That’s more than double the amount we ate just 40 years ago. The top four poultry firms control almost 60% of the market. You may have heard of them. Pilgrim’s Pride Tyson, Perdue and Sanderson Farms.

FOLEY: Yeah, that’s such a poignant example of what’s meant by corporate concentration, right? When production in one industry is concentrated in the hands of so few companies, Hearing from Dave Matthews earlier, I realize we’re lucky that farm aid artists understand the intricacies of this kind of farming. To dive deeper into what it’s really like to be a farmer in this situation, we called up Craig Watts, who’s a former contract poultry grower.

WATTS: My name is Craig Watts and I live on my family farm that has been in our family since we have a land grant from the king of England, wo we’ve been here a while. I am a recovering factory farmer raised chickens for 23.5 years on a contract for Perdue farms, got out of that in 2016, kind of shifted my production to something smaller and more enjoyable and then got into some advocacy too. It’s a lot better on this side than it was from the inside looking out.

FOLEY: Craig grew up on a farm in Southeast North Carolina. As a young man, he left farming for a while and then caught the bug and came back home to that same farm in North Carolina. This was in the early 1990s.

WATTS: If you’d asked me 10 years prior to that, I would have never wanted to see the farm again. But I had this strong longing to get back. Starting a row crop operation, it made no sense with our small acreage and the price of equipment. So that was the exact moment the chicken companies came in and were courting farmers to build the houses. And you know, it looked like a much better deal than a row crop operation that showed positive cash flow from day one, I could get financed fairly easily. I have a strong agricultural background. I had a business degree. It just seemed like a perfect fit.

KURN: “Seemed” like the perfect fit is really the key here because in reality, Craig got pulled into a system that took advantage of him and his family farm.

WATTS: The way it works is the farmer borrows the money. He has the land, he puts the buildings up. They are built to these integrators (meaning company, but like Tyson Purdue Smithfield, those types of companies). So we build to their specifications and we sign a contract and once the buildings are ready, they bring out birds. They own the birds, they own the feed, they own the vaccination program. We basically just sell our labor and we paid all the utilities and the help and all that kind of stuff. John Oliver put it best,

JOHN OLIVER: You own the property and the equipment, we own the chickens. That essentially means you own everything that costs money and we own everything that makes money.

FOLEY: That was John Oliver back in 2015 talking about the problems with the poultry industry on his show, Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. And if what Craig is talking about doesn’t sound burdensome enough. The farmers are caught in what the industry calls a tournament system, a system that’s completely rigged in the company’s favor and forces farmers to compete among each other.

WATTS: When I say I was a serf on my own land, the contracts are – I hesitate to call them contracts because the contract would indicate mutual obligation. They are actually just agreements. I agree to do anything they tell me to do. And when they pulled up on my farm, I might as well have just handed them the keys and went home because I had no control over what went on in that grow-out program. I was just basically handed a list: do it this way or we won’t come back your way anymore. So you wind up being a serf with the mortgages, I think is what a lot of people call it

KURN: When the money trickles down. How much do the farmers actually make for that type of system?

WATTS: That’s the thing. It’s as unpredictable as the weather. There’s this Grand Ponzi scheme, they call it the tournament system where they pit farmer against farmer. And supposedly it’s, solely based on that farmer’s management skills. But the inputs that control how that farm performs are the birds and the feed which the company owns. So there’s a lot that happens before that farmer ever sees that bird. If you get bad chicks, you’re not gonna do well, I mean, competition is competition. Like if, if Michael and I are racing, and we start at the same spot and run to another spot, the winner is the winner. If I back up 10 yards, Michael’s gonna beat me every time. That’s like a farmer getting bad chicks. Right. That’s the nature of the beast, though. It was very unpredictable from flock to flock and year to year.

KURN: The farmers are really getting the short end of the stick. But so are the consumers and the environment. Do you remember how Craig told us about the terrible conditions that they had to create so that their farm was consistent with other farms?

FOLEY: Right, it was awful. The animals are kept inside without ever seeing the light of day in tiny spaces where they can’t move. 30,000 chickens in 20,000 square feet. That’s 0.67 square feet per chicken, which is basically the size of a piece of notebook paper. The environmental impacts of the waste being funneled out, to the air to the soil, the water are practically immeasurable as is the public health tool on the neighbors.

KURN: The manure produced is no joke. It contains pathogens such as E coli and also antibiotics and chemical additives, among other things that we really don’t want leaching into our groundwater. The amount produced is also truly wild. Here’s something that I found: the Government Accountability Office has some staggering numbers. They report that livestock animals in the US produce between three and 20 times more waste than people in the US produced each year. And remember, the vast majority of livestock animals in the US live in CAFOs.

FOLEY: Phew, or I guess P-ew! Besides the waste and other issues, Craig really started seeing the light when this scheme did not in fact get him out of debt.

WATTS: Then I built two more houses, and my money didn’t double, and my expenses more than doubled. So I knew right then I had been had. I was a half a million dollars in debt.

FOLEY: Getting out of the system is not as easy as quitting most jobs. Craig had that incredible debt and was under contract. So we asked him, how did he get out?

WATTS: I was sitting in a motel room in Brookings, South Dakota, and a Perdue commercial came on and it’s Jim Perdue and he’s driving down the road and he’s talking about how well his father told him to treat his people, and he steps inside that chicken house, and it looks like the feed pans have been wiped down with Armor All. Everything is shiny. The birds are beautiful white big chickens. They look like they got a half an acre to roam around in. Fresh pine shavings on market age birds. It don’t look like that, I promise you. And I’m sitting thinking, wow, ok, I gotta do something. Yes, I had a contract to raise birds for Perdue Farms but, but I am a farmer, right? Ultimately, the boss is the consumer and I just felt like they were getting hoodwinked and they deserve to know better.

KURN : The way Craig got out of the system is a very long story. But ultimately, he got in touch with Leah Garces, an animal welfare activist who came to his farm to learn more.

WATTS: I was dirt poor farmer from podunk, North Carolina. She’s bright lights, big city from Atlanta, Georgia. She’s an animal rights person. And I’m a farmer – we’re not supposed to get along. But when we sat down and we started telling our stories, 98% was the same story. So we just decided to take a chance. She said, can I come film? I said, absolutely. And so she brought a, a lady down here and, and, and it was a five minute YouTube, but the New York Times picked it up, A guy named Nick Kristof, who’s like a big deal.

FOLEY: And Craig started talking to other reporters and talk show hosts, but of course, Perdue got wind of this and didn’t like it one bit. That’s when the retaliation started. The company gave him bad birds, told him he was a bad producer, and sent him letters about being on probation and such.

WATTS: It was about a year after that all that happened, and, I just was sitting on the end of the bed like this, my head in my hands, about two o’clock in the morning waiting for my wife to wake up. She woke up about five. I said, “can I quit this?” She said, “I told you that two years ago,” but I couldn’t have done it two years ago because we were still so, so much in debt. We always call it the debt treadmill because once you get the houses kind of paid down, then they’re gonna come out and they’re gonna make these demands for you to spend more money on new equipment, and it’s just continuous debt. And I was 50 years old. It was hard starting life back over at 50, but I didn’t want to wait to 60.

FOLEY: Nearly a decade later, Craig, who Whistleblower Insider named the 2015 whistleblower of the year, right – nearly a decade after this, he’s still pursuing legal relief against Perdue because, he says, they violated protected activity under whistleblower laws. But unlike many other farmers, fortunately, Craig was able to get out of contract farming, and now he works to help other farmers in similar situations.

We really want to drill down on how our agriculture system went from idyllic pastures and barnyards to industrial scale row houses filled with chickens or hogs packed so closely together that antibiotics are a necessity just to keep diseases at bay. So we caught up with Tim Gibbons of the Missouri Rural Crisis Center. He’s a longtime friend of Farm Aid and an amazing organizer.

KURN : Tim told us that in the US, Missouri is second only to Texas in farming operations also second only to Texas in cattle operations. And that, as recently as the 1990s, Missouri was a national leader in hog operations.

GIBBONS: A lot of our members used to raise hogs and, you know, we’ve seen what’s happened to the hog industry specifically in the late eighties, and through the nineties: the vast majority, nearly 90% of Missouri hog producers were put out of business in one generation. Over 80% of US hog producers were put out of business in one generation.

FOLEY: You had hog farmers in Missouri for centuries, right? What was the mechanism by which they started to get squeezed and overtaken by corporate agribusiness?

GIBBONS: That’s a good question. You know, hog production in Missouri has been historically, you know, economic driver in our local communities. Why was that a big deal in Missouri? First of all, you didn’t need a lot of land to raise hogs so you could raise them on small plots of land. They grew out quickly. So hog farmers jumped in and out of the market based upon where the price was. So when prices were low, they jumped out of the market and when prices were high, they jumped into the market, and that created a self-regulating marketplace, truly, you know, a marketplace that was designed based upon supply and demand. That’s what capitalism is supposed to be all about. What happened was in the late eighties and early nineties policies and specifically, you know, millions and now billions of dollars of our taxpayer money has fueled the industrial corporate takeover of the hog industry. It fueled industrialization, it fueled hogs being grown out in huge barns. And, and not just, you know, hundreds of hogs but thousands and tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands of hogs. And what that did is it created overproduction. So they intentionally overproduce within the marketplace. And what overproduction does is keeps the price artificially always low. And when prices are always low, that kicked all the farmers, all the independent hog farmers, out of the market. They could no longer compete.

KURN: So basically hog farming and chicken farming followed the same track into industrial scale production. The independent family farmers who used to raise chickens and pigs were pushed out of the market, leaving behind only a few mega corporations to rule the marketplace. Sound familiar?

GIBBONS: Right now, we have four corporations that control over 70% of the hog marketplace, and 50% of the hog marketplace is controlled by two foreign multinational corporations: JBS out of Brazil and Smithfield out of China. But they always have a buyer, they always have a buyer in the US government, the US government through the Agriculture Marketing Service buys, you know, millions and billions of dollars worth of pork to feed, you know, the government programs, and they’re vertically integrated, so they can make money on multiple parts of the supply chain.

FOLEY: Right, so I’m a historian. So this reminds me of the 19th century, right? This sounds like the oil industry when companies like Standard Oil wiped out local and regional producers by selling oil at such low prices that the little guys could not compete. And once the competition was wiped out, Standard Oil and a few other companies controlled the market, not just in the US, but internationally. So now it’s the pork, the beef, the chicken industries that are following that model. And as Tim points out, it’s not like it’s because they’re good guys trying to feed the world.

GIBBONS: I think right now and, specifically, since COVID, we’ve seen how they’re making record profits quarter after quarter because of quote unquote supply chain issues, but also corporate greed. They also control policies that influence trade, so their ability to globalize price and globalize the protein marketplace – these are multinational billion-dollar corporations that are buying meat all over the world that are producing meat all over the world – and they’re able to manipulate markets in, in countries all over the world for their own benefit. One example, within the cattle market: in 2022 we imported 3.4 billion lbs. of boxed beef, and we imported 1.6 million live cattle from all over the world – live cattle, mostly from Canada and Mexico, but boxed beef from all over the world, Brazil and Nicaragua…And what that allows these traders to do, and these meat packers to do, is undercut farmers not only in our country but in countries all over, all over our world.

KURN: Well, this is all pretty grim, not only is it devastating for our family farmers and have grave consequences for our environment, but it also raises a lot of questions about who controls the land, questions we’ll get into in future episodes. But this kind of control over the food we eat is obviously not good for us as eaters, as ordinary people trying to put healthy food on the table for our families.

GIBBONS: These corporations don’t care about farmers, they don’t care about consumers. They don’t care about our land, our water. They don’t care about our fight for democracy, and, actually, they would prefer us not to have democracy and, you know, them just writing all the rules at the expense of all of us.

FOLEY: Well, the good news is that now that we’ve dragged you down into the filthy lagoon of industrialized agriculture. We get to talk about what folks are doing to get us out of it, to change this filthy, rotten system. So stay tuned.

KURN: Welcome back. You know, Michael, listening to Craig and Tim talk about the industrial agriculture system, it’s hard not to think about the work that Farm Aid and our allies were doing back in the 1990s to confront what everyone then called factory farming.

FOLEY: Yeah, exactly. Although Farm Aid started out trying to help fend off farm foreclosures and keep banks from pushing farmers off the land in the 1980s, by the nineties, Willie Nelson and Neil Young and John Mellencamp were joining thousands of farmers in protesting against Kos being built in farm country.

KURN: I know. I love that image that you recently dug up from our archives. It’s an image of Willie and his sister Bobbie setting up to perform at the farm protests in Lincoln Township, Missouri in 1995. It was a great photo. And actually, if anyone wants to see it, you can see it on our website. These high-profile challenges to factory farming in the nineties were not enough to end the practice. There are still many organizations working hard to change the system of agriculture in this country. Here again, is Tim Gibbons.

GIBBONS: Organizations like Farm Aid and organizations like Missouri Royal Crisis Center and our allies have been working on these issues for literally decades. One of the main purposes of our federal government is to enforce antitrust law so that there’s competition in our marketplace. I mean, this isn’t just me saying this, this goes back to Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations. You know, the father of Laissez Faire, free market capitalism. You can’t have monopolistic control of markets and have free market capitalism. It doesn’t work. And you also can’t have monopolistic control and truly have a Representative Democratic process.

KURN : The Farm Bill is one of the places to make significant change. Our allies are trying to make headway there.

GIBBONS: The Farm Bill is a policy driver for the things that we’re talking about right now. We need policies to be much different in our Farm Bill. We do not need a status quo Farm Bill. Instead, we need to funnel money to independent family farmers so that they can be be stewards of the land, have conservation on their land. But also, you know, support their local economies. This is also important for consumers. Because right now when, when, when just a few multinational corporations control the market, what they can do is they can charge whatever the market will quote-unquote bear. So they’ll charge as much as they can until they get a little push back, you know? So they’re trying to, to have that they spread as broad as possible. And that spread means, you know, their goal is to pay producers less, charge consumers more and, and make more of that money in the middle.

KURN: The Farm Bill was supposed to be renewed this past September, but the Senate recently passed the House continuing resolution to extend the 2018 farm bill through September 2024. So we have a little less than a year to push for the change we want to see.

GIBBONS: We need policies that are written by and for farmers and consumers and, you know, make greed and extraction of wealth not the priority, but instead our local economies and our, and our US economy as a whole. Who’s gonna own that land later? Is it gonna be family, farmers and local people and Missourians and people, you know, in Iowa, are Iowans gonna own it in Minnesota, are Minnesotan’s gonna own it? Or is it gonna be Wall Street? Is it gonna be absentee owners? Is it gonna be, you know, Chinese multinational corporations or Brazilian multinational corporations? We know that’s not our values, and we don’t think that’s good for our country.

FOLEY: We’re gonna spend more time digging into the Farm Bill in upcoming episodes of against the grain. But we want to pivot to what can all of us do? Is there any hope?

KURN: So, for our listeners – is there anything that they can do?

GIBBONS: Yeah, there’s lots of things that we can do together. I mean, one of MRCC’s slogans is “working together to make a difference.” First and foremost, there is no silver bullet to fix this problem. There have been lots of things that have created the issue, the problem that we’re in, and the system that we’re in right now. We’re gonna need, you know, a lot of policy prescriptions and, and, and solutions coming out of it.

GIBBONS: One thing is buy locally, you know, buy from your family farmer. Support local restaurants that support local family farmers. Ask grocery stores to support local family farmers. We also need to demand from our elected representatives that they actually represent us, that they represent the vast majority of us. So when we’re voters, when we go to campaign events, when we talk to, you know, our state reps who may be, you know, in Congress someday, when we talk to people in the media, we need to talk about these issues. What I know being an organizer for now 20 years, and being an organizer that works with mostly farmers and rural people, but also brings people in the same room from vastly different political, ideological, the ideological spectrum, is when we bring people in the same room and talk about these issues, everybody’s shaking their head, Yes. And, and that tells me that we’re telling the truth, that we’re actually listening, and that people agree with us on these really large issues that impact all of our lives,

FOLEY: I love that. These are all things that we can all do, right? We can all contact our elected officials, we can buy locally. We have lots more ideas that you can share with everybody – your friends, your family – that are gonna be available on our website.

KURN: And when we do these things, we know we’ll be joining forces with people who are finding hope in our farm and food future, including some notable farm aid artists.

FOLEY: That’s right. We caught up with frequent Farm Aid artist, Allison Russell, just before this year’s festival, and I love the way she framed the struggle.

RUSSELL: I’m Alison Russell. I’m a mother, a musician, an activist, an author, an artist. And I live now in Nashville, Tennessee, but I’m from Montreal Quebec Canada. I’m a Scottish-Grenadian-Canadian, a Queer black new immigrant to America. And I believe very deeply in the harm reduction work that Farm Aid is engaged in. And I’m particularly excited about climate resilient farming techniques and the small, transformative family farms that are springing up everywhere to help pull us out of the tailspin of intense and potentially species-ending abusive extractive practices that we have been trapped in for too long.

KURN: Allison, like many other artists, authors and political activists points out that we really can vote each and every day.

FOLEY: Right, I’d venture to say three times a day. Craig Watts said to us that we vote with our forks three times a day.

RUSSELL: I think it’s significant: Where do we put our dollars and what are the political ramifications of where we put those dollars? If we are putting our dollars into massive extractive factory farms that, for example, I think about as a touring artist who’s driven up and down the I-5, all of my career, it just makes you despair of humanity when you drive by this. It’s a massive, massive factory farm where cattle are kept in completely inhumane circumstances. Any artist that’s driven the I-5 knows when it’s miles and miles of cattle, just packed, shoulder to shoulder in completely unsanitary, inhumane, unsustainable conditions, and the difference between that – and I just did a tour of Ireland opening for a wonderful artist called Hozier. And there’s no such thing as a factory farm in Ireland. And you drive through the rolling countryside. It smells beautiful. There’s green, rolling hills. They’re the happiest cows you’ve ever seen in your life. And when you go in and eat a meal, it is a palpable difference. If we don’t get our food supply right, it so exponentially harmfully impacts every other thing that we’re facing.

KURN: It’s awesome how Allison frames the solution as harm reduction and of course, who doesn’t want to reduce harm? Do you want to do something about this situation? Take action? Head to our website where we have a way for you to do that. You can tell the federal government to improve their buying practices and address their role in this whole corporate concentration mess.

FOLEY: Go to www.farmaid.org/podcast. There, you’ll find a link to the action Jessica is talking about.

KURN: While you’re on our website, check out photos from these interviews, including backstage pictures with Dave Matthews. We also have archival video and music from this episode.

FOLEY: In our next episode, we’ll talk about black land loss and issues of indigenous land and knowledge and agriculture. And what’s something you want to hear about? We’d love to hear from you. So please write to us at podcast@farmaid.org

KURN: For all the things we’ve mentioned and to get involved, be sure to visit our website again. That’s www.farmaid.org/podcast. Against the Grain was written and produced by us, with sound editing by Blurry Cowboy Media. Our theme music was written and performed by Micah Nelson.

FOLEY: And thanks so much to our guests: to Dave Matthews, Alison Russell, Tim Gibbons and Craig Watts, for speaking with us. Be sure to check out Dave and Alison on tour and listen to Alison’s brilliant new album, The Returner. Thanks so much for listening.

KURN: We’ll chat with you next time!

FOLEY: Patagonia Workwear, durable, timeless gear built for the ones who prove that food production, skilled trades, construction and ecosystem restoration can and should cause the least amount of harm. Patagonia workwear believes that it is possible to make a good living on a living planet.

Photo Gallery